Little or nothing we know about the history of Chile before the Spanish occupation. The northern half belonged to the Peruvian kingdom of the Incas. But once Peru was subjugated and erected viceroyalty, the Chilean region also became Spanish dominion.

Thus the story began with the conquest of this land by the Spanish explorer Diego de Almagro who in 1535 first penetrated it through the heights of the Bolivian Andes. But after the failure of his expedition and his catastrophic results, no one ventured into that area for two years.

In 1539, after having agreed with Pizarro, another Spaniard, Pedro de Valdivia, undertook the conquest of the territory in the name of the Crown of Spain. In January 1540 he left Cuzco with a retinue of 150 Spaniards and 1,000 Indians and, after six months, arrived on the banks of the Mapocho, at the foot of the Huelen hill, he founded the city of Santiago de la Nueva Extremadura, in memory of his city Christmas, Santiago de Compostela. It was February 12, 1541.

The search for gold began immediately in the Malga – Malga river and while the Spaniards were directing, the Indians worked in such pitiful conditions that in September of that same year they rebelled causing great damage to the Spaniards, with the assault on Santiago.

Alonso de Monroy had to be sent to Peru to ask for help. He returned with arms and supplies only after two years, in 1543.

The Spanish domination in Chile was much more difficult than elsewhere, and could never be said to be safe, since the Araucani Indians could not stand the conquerors and, thus, led by Lautaro, led a ruthless guerrilla war against them which, which began in 1543, continued almost continuously, with ups and downs, until the end of the eighteenth century. As soon as the opportunity arose, they fled to the south, leaving the areas around Santiago almost deserted and, therefore, the soil could not be exploited due to lack of workers. It was therefore necessary to extend the conquest to the south and so, in September 1544, arrived in the Coquimbo Valley, the Spaniards founded La Serena.

Almost simultaneously the Genoese Giovan Battista Pastene, appointed admiral by Valdivia, occupied the San Pedro bay. Valdivia, in turn, in 1546 advanced to the Bio-Bio river.

Soon the natives destroyed La Sirena; then another expedition became necessary, commanded by Francisco de Aguire with the task of subduing the rebels and rebuilding the town.

In 1550 Valdivia returned to the south and at the mouth of the Bio-Bio river he founded the city of Concepcion (March) and defeated the Araucans, at least apparently returning calm everywhere.

In 1552 two other cities arose: that of Valdivia and that of Villarrica. In 1553, however, the city of Santiago del Estero was founded on the other side of the Andes.

What had only been apparent calm did not last long and as of January 1, 1553 Valdivia was surprised and captured in Tucapel and immediately sentenced to death. In February of the year after his lieutenant Villagra, he suffered another defeat; in December 1555 Concepcion fell into the hands of the Araucans who, always led by Lautaro, moved against Santiago.

They were, however, rejected; Lautaro fell into battle on April 29, 1557 and in August of the same year the new Governor, Don Garcia Hurtado de Mendoza, beat the Indians, recaptured the lost lands, founded new centers such as Osorno and Mendoza and reached the Chiloè archipelago, the northernmost island of Patagonia. But the rebellions were never definitively tamed and the Indians in 1559 destroyed six cities; in 1654 there was a disastrous general uprising for the whole colony, which was then ruled by a Governor, flanked by the “Audiencia” and by an advisory body, made up of six judges and a regent, who ruled on administrative and legal matters.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, the relations between the Spaniards and Araucans having slightly softened, a phase of progress began in the colony so that in 1712, in eight months, 30 ships loaded with wheat sailed from the port of Valparaiso, to Europe, and ten others from the port of Concepcion.

But the Araucanians’ thirst for freedom had not quenched and, in 1723, a bloody revolt broke out which caused considerable damage to the colony; most of the crops were set on fire. From Spain governors always came, of great military experience, but they were never able to advance the country that had to be always supplied with everything, costing the Crown so much that more than once the Spanish court spoke of abandon such an expensive conquest.

Whether the Spaniards proposed with massacres and repressions, or that they proposed with peaceful systems, the Araucans never submitted. Indeed, once a peace initiative had been undertaken by the Jesuit missionary Luis de Valdivia, sent by King Philip III, it had the opposite effect and ended with the killing of three missionaries, because a Spanish delegate who had accompanied the Jesuit he had held an attitude which they had deemed offensive. This episode reopened hostilities.

In the meantime, between one battle and the next, efforts were being made to reduce the economic liability that Chile procured for Spain; the search for gold had proved unsuccessful. Then priority was given to the extraction, and therefore, to the export of copper which left from Coquimbo to Peru and Spain itself. Agriculture was also flourishing, producing hemp, cereals, wine, oil, fruit; all fueling the export.

But to have bigger benefits more people would be able to work. The natives were scarce, above all for the continuous wars, the black slaves were too expensive and the whites were in small numbers and rather dedicated to get rich. Then there was the clergy who provided for the education and conversion of the natives, with poor results, but with the accumulation of personal profits, which annoyed the laity.

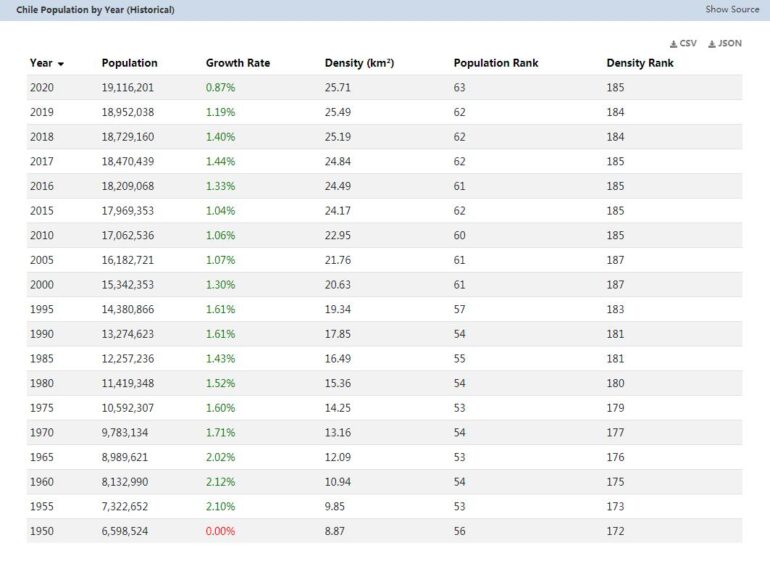

In this period, however, there was also progress in trade, the population grew, the coffers of the colony experienced greater income and also cultural life experienced a greater flowering. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Chile.

In 1747 the University of San Felipe was founded with important chairs such as grammar, philosophy, legislation, canon law, theology, mathematics and medicine. Courses began in 1756 and were held by the Jesuits until 1767 when the ministers of King Charles III of Spain expelled them from Chile.

Meanwhile, the economic conditions created more and more contrasts between the Creoles and the Spaniards and underneath it began to meander, along with the discontent, also another sentiment, the national one, to the awakening of which the foreigners contributed, first among all the North Americans.

While frequenting the ports of Chile for commercial exchanges, they stirred up the populations by letting them know the constitution of the republic after the declaration of independence from England.

In 1788 an Irishman, Ambrose O’Higgins, had been appointed Governor, who worked very hard for the development of the colony; he had the cities embellished, founded the “Academy of Sciences, Drawing and Living Languages”, had a theater built in Santiago and freed the slave Indians.

As already happened in other areas of North America, even in Chile the Spanish colonists had given themselves a new homeland, they had changed their lives and aspired to free themselves from Spain.

Suddenly, towards the end of 1809, rumors of the collapse of the throne of Spain by Napoleon I came to them. It was the occasion that the liberal colonists waited to start a riot in Chile.

The governor of the colony, in agreement with the leaders of the independentists, appointed a “Congress” that would temporarily rule the fate of the country, while Chile continued to recognize the sovereignty of King Ferdinand VII who, instead, had been ousted by Napoleon. After two years this Congress was abolished and the government completely passed into the hands of the Chilean liberals, thanks to General Josè Miguel Carrera, who was the hero of the “Old Homeland”, as Chile was called between the years 1811 and 1814, years in which for the first time an autonomous government took place.

Carrera, bold and energetic, had concluded the armed revolt against Spain in just twenty days, becoming national hero and head of the country; but he was a dictator and following the intrigues of his political rivals he was forced to leave the country.

During the period of exile he continually moved from one end of the Americas to the other in search of aid to regain power. And when, with the help of the Argentine government, he had already collected men and weapons to attempt the feat, he fell into the hands of his enemies who executed him.

Power had passed into the hands of liberal and moderate men. Thus on February 12, 1818 the Independent Republic of Chile was proclaimed proclaimed by O’Higgins, who a year later, for patriotic merits, had been declared “Supreme Director” of Chile.

But the Spaniards attempted to regain power and defeat the patriots in Cancha Rayada on March 19, 1818. All their illusions fell definitively on April 8 of the same year, after the defeat suffered in Maipo, by General Josè de San Martin, half of the glory is due to the heart for the liberation of South America; the other half belongs to Simon Bolivar by right.

The first Chief of Free Chile, O’Higgins, with his authoritarian and imperious character, while deepening all his strength for the development of the country, aroused discontent to the point that, invited by the notables of Santiago to present himself before the Assembly, on January 28, 1823, he resigned. He was succeeded by General Ramon Freire who had the First Constitution of Chile voted and definitively abolished slavery.

But the country was going through a period of unease; the various parties that arose were always at odds with each other, discontent was winding and in July 1826 Freire also resigned from office.

Two short presidencies followed, that of Blanco Encalada and Agostino Eyzaguirre, then Freire returned to office for only three months. The successor Francisco A. Pinto underwent a revolutionary movement in 1830 that got the better of the battle of Lircay and overthrew it. After that, and for a decade (1831-1841), power was taken by General Joaquin Prieto, conservative, and after him by General Manuel Bulnes (1841-1851) and Manuel Montt (1851-1861). In all these years, power was concentrated in the hands of very few men who severely restricted public freedoms and forcibly shattered all oppositions.

The Constitution of 1828, the work of the liberals, had decentralized administrative power, curbed executive power by not allowing the re-election of a president after five years and had given powers to Congress.

That of 1833 had undergone significant changes according to which the power returned to the center, the provincial intendants who had to manage it were appointed directly by the President of the Republic, who also gave special duties to the various governors and to the minor local leaders. The President was surrounded by four ministers: Interior, Foreign, Justice, Worship and Public Education and that of the Marine War, Finance and Treasury. Then he was assisted by a Council of State, made up of twelve members, who had the task of drafting the laws and compiling the budgets.

Despite the liberal movements that occurred in 1835, 1851 and 1859, the government experienced a period of stability during which it could progress by virtue of the creation of banks and the stipulation of several international trade treaties. Cultural institutes were opened, including the University of Santiago, the exploitation of the silver mines in Copiapò and the coal mines of Lota was strengthened, railways and telegraphs were built and a great boost was given to the colonization of the province of Valdivia to work of German colonizers; the Strait of Magellan was occupied, the port of Valparaiso expanded. In 1857 the civil code and the commercial code were promulgated, then a remarkable structure was given to the Catholic Church.

The greatest credit for all this went to Montt who was first Minister of President Bulnes and then President himself.

In 1861 Josè Joaquin Perez was elected, a man of liberal views and also his successors, among whom Anibal Pinto (1876/1881) had the best collaborators among the liberals. In 1865/66, Chile found itself facing new Spanish claims by collaborating with Peru. The experience gained from this convinced the government bodies that it was necessary to strengthen the army, but above all the navy given the thousands of kilometers of coast that go from north to south. Also in 1866 he went to war with Bolivia and conquered the port of Antofagasta along the Pacific coast, important for the very rich deposits of silver, copper and saltpetre and with significant deposits of guano. In this war, the navy of Chile, modern and fully strengthened, contributed almost completely to the achievement of the conquests.

In the meantime it had come to 1881; the mandate of President Pinto expired and he was succeeded by the liberal Domingo Santa Maria who was opposed by conservatives and even by a part of liberal dissidents because he had allowed some laws that introduced civil marriage, birth and death registers and opened cemeteries to all cults. Despite everything, he was able to keep his mandate until his natural expiry in 1886.

He was succeeded by a liberal, Manuel Balmaceda, who wanted to rebuild the liberal party. And then, convinced that he had a majority, he implemented a policy of heavy expenses: he built many railway lines in the south, schools and colleges, increased the fleet of several units, built a naval base in Talcahuano, armed the infantry and artillery and precisely with heavy artillery he fortified the cities of Valparaiso, Talcahuano and Iquique. All these expenses could be incurred because the country was going through a flourishing period and the exploitation of the Antofagasta and Tarapacà fields gave remarkable results.

Balmaceda, in his time, had created a ministry that allowed him to reach the majority by directly electing the ministers of his liking, while the opposition demanded that regular elections be held with the application of a real parliamentary regime.

There was a violent clash, the rebels elected a temporary “Junta”, seized the main northern ports and, with the support of the navy, beat the troops loyal to Balmaceda in the battle of Placilla; he had to abandon power and committed suicide on September 19, 1891.

The head of the “Giunta”, Admiral Montt, elected president, immediately took care of pacifying the country by granting an amnesty to all Balmaceda officers, who thus returned to their homeland; granted autonomy to local administrations, reconstituted the army by placing German officers at its head and restored the gold currency.

In 1896 F. Errazuriz Echaurren became president and, immediately at the beginning of the following year, he found himself facing Bolivia. And even inside there had been major changes in the government structure. Practically power was in the hands of Congress (formed by the Senate and the Chamber of Deputies) which was thus the only arbiter of Chile’s politics.