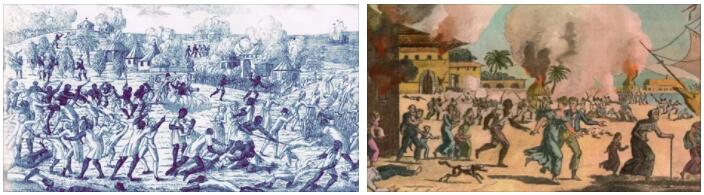

According to shopareview, the island of Haiti was of great importance in the early days of the conquest of America; but it soon decayed, as the colonists headed mainly to Mexico and Peru, and it was almost abandoned. The incursions of the English, French and Dutch freebooters contributed to this fact. Around 1630 French corsairs settled on Tortuga Island, from which they frequently attacked the Spaniards of Haiti, gradually settling in the N. and the island continued to remain under Spanish rule; see san domingo). The official recognition of the mother country also came, with the appointment, made by Louis XIV, of the governor Bertrand d’Ogeron (1661); and in the Peace of Ryswick of 1697 the new colony, which formed nearly a third of the island, in its western part, was officially recognized by Spain. The repercussions of the Revolution at the end of the century were profound in this distant French colony. XVIII. Already when Louis XVI had summoned the States General, popular assemblies were organized in the colony, despite the prohibition of the governor, Marquis du Chilleau; who, believing that they had the right to send deputies to the States General, elected 18. On their arrival in France, they found the states transformed into a constituent assembly, and were admitted to the assembly only in number of six. Then when the slaves of the colony learned that the Assembly had approved, on August 20, 1789, the declaration of human rights, they thought that the time had come for their liberation; but the settlers of the North gathered in assembly and opposed that claim, threatening to proclaim the independence of the colony. Therefore the Paris Convention declared on March 8, 1790 that it did not intend to include the colonies in the constitution granted to the metropolises. On April 16 of that same year a general assembly met in the city of Saint-Marc, in which the foundations for the future constitution of the colony were established; but the governor, Count de Peynier, decreed the dissolution of the Assembly and accused its members of treason for having conceived plans for independence, ordering Colonel Mauduit to forcibly dissolve the West Provincial Assembly. This was done; and later the Mauduit went to the city of Saint-Marc to dissolve the General Assembly there. The deputies fled; 85 of them went to France, where the National Assembly had them detained. The “amis des Noirs” philanthropists of England and France sent the mulatto Vincent Ogé, a native of the island, who was in France, to the colony. the revolt, but defeated and fallen into the hands of the French, on March 26, 1791 he was executed along with 20 other comrades. The equality of the rights of the Negroes and the Whites of the colonies, decreed by the French National Assembly, produced in the isolates a deep indignation among the settlers; and then Negroes and mulattoes rebelled openly. On the night of 22 August 1791, 4000 Negroes began the insurrection in the surroundings of the Cap-Français, spread it to the neighboring countryside and, despite the resistance of the settlers, remained masters of the plain of the Cap and the nearby mountains. In other provinces, too, rebellion had broken out; the Whites were powerless to subdue the rebels, who sacked Port-Saint-Louis and burned Portau-Prince. The news of these events made a great impression in France, and the Legislative Assembly declared on February 28, 1792, that all political rights should be immediately granted to Negroes and mulattos. An expedition of 8000 men under the command of three commissioners of the Assembly arrived on the island; Governor Blanchelande was deposed and the Colonial Assembly was replaced by a twelve-member commission made up of Whites and black men. General Galbaud, who had arrived on the island with the title of governor, was forced to return to France; but he remained in the port of Cap-Français, and, posting himself at the head of the discontented colonists, attacked the commissioners, who called for help to the Negroes who, commanded by Macaya, took possession of the city of Cap-Français and burned the city. The settlers who were able to escape asked for help from England, which sent 700 men commanded by Whiteloque, who took possession of Port-au-Prince on June 5, 1794. The Negroes, commanded by the Negro Toussaint Louverture, supported the war with the English for two years, aided by the French government. In the’ April 1798 General Maitlan took command of the English army; but on May 9 he was forced to conclude an agreement with the Negro commander, according to which he renounced the conquest. Toussaint Louverture acquired almost unlimited power on the island, established the Catholic cult and disciplined an army of 60,000 men. He also occupied the Spanish part of the island, which by the Treaty of Basel of 1795 was to pass under French rule, and called an assembly which approved and sanctioned a constitution on 1 July 1801 in which it was declared that the colony was part of the French Republic. Nevertheless Napoleon sent an expedition against the island commanded by General Leclerc, who sent Toussaint Louverture to France; imprisoned in Besançon, he died there on April 27, 1803. The Negroes continued the struggle, under the command of Dessalines; the French army was forced to capitulate, and the island proclaimed its independence on January 1, 1804, giving the new republic the name of Haiti and appointing Dessalines governor for life, who nine months later had himself crowned emperor under the name of James I (September 2, 1804). A revolt broke out against him under the leadership of the mulatto Alessandro Pétion and the negro Enrico Christophe; Dessalines perished in 1806 in an ambush; Christophe, proclaimed president, in 1811 took the title of king under the name of Henry I, while Pétion was appointed governor of Port-au-Prince. Having also come to war with each other, Pétion proclaimed a republic in the southern part of the island and, dying in 1818, left to his successor, Jean-Pierre Boyer, a prosperous and peaceful state; instead Christophe, hated by his subjects, had to flee in 1820. Boyer, proclaimed president in 1822, became master of the whole island; but in the year 1843 he was sent into exile by a revolution, and the republic of San Domingo (v.) proclaimed independence from that of Haiti in May 1844. Boyer was succeeded by Hérard Rivière and others, and finally the negro Faustino Soulouque, who in 1849 had himself proclaimed emperor under the name of Faustino I; but he was deposed in 1859 by a revolution, which re-established the republic under the presidency of Fabre Goffrard. From 1886, when General Salomon had completed the term of his presidency, until 1915, all but one presidents were deposed by revolutions; and in 1915 there were riots, which resulted in the assassination of President Vilbrun Guillaum Sam. On July 28 of the same year, US troops landed on the island, under whose protection Congress elected Sudre Dartiguenave as president. To reorganize the island, however, the North American occupation was proclaimed for some time. In 1922 Luigi Borno, the new president (later re-elected in 1926), signed a loan with the Washington government, and to him we owe the gigantic steps taken by Haiti. The last president, Stenio Vincent, took office on November 18, 1930.