The first European who saw the coasts of Argentina was the Italian Amerigo Vespucci, in 1501, when he sailed along the coasts of the continent to Tierra del Fuego. But the first to land on the island of Martin Garcia, on the banks of the river which he immediately called Rio de Solis, was Juan Diaz de Solis, Spain’s senior pilot.

On one night in 1516, while with the men of his expedition he was bivouacking near the banks of the river, in the middle of a swamp in the tropical forest, the fierce Indios Charruas arrived, invisible as shadows, who killed them all. With this tragic episode, the history of Argentina practically opens.

The river was called in two different ways: “Rio da Prata” in Portuguese and “Rio de la Plata” in Spanish, that is silver river because the natives used silver ornaments and Europeans deduced that the area was rich in silver deposits.

After the expedition of the unfortunate de Solis there was that of Magellan, a Portuguese serving Spain. His fleet entered the Plata estuary to carry out surveys and so one of his ships, the Santiago, commanded by Juan Serrano, discovered the Uruguay river (1519/1520), and went up it.

In May 1527 the Venetian navigator Sebastiano Caboto arrived there, who opened the way to European penetration by climbing the Plata and the Paranà, on whose banks he founded the fort of Santo Spirito.

Then Caboto returned to his home base and had to overcome a conflict that broke out with Diego Garcia, companion of Vespucci, Solis and Magellan, who took credit for the exploration of the Rio de Solis. When the conflict was settled, Cabot resumed sailing on the Paraguay River; the Indians occupied the Santo Spirito fort and Cabot returned to Spain (1530).

Four years later (1534) news spread of the discovery of immense wealth in Peru, conquered by Pizarro, and since Rio de la Plata was considered the easiest way to reach that territory, Spain sent other conquerors to take possession of the banks of that river, above all to thwart the passage to the Portuguese navigators.

Spain and Portugal were linked by the Tordesillas Pact which regulated the division of the discovered lands among them. Since, however, the Portuguese had repeatedly tried to ignore this pact, Spain in 1535 hastened to send a new expedition, under the orders of Pedro de Mendoza, whom Charles V had named “Governor General of the Rio de la Plata lands”.

In 1536, in early February, de Mendoza founded, on the bank of a small river, the Riachuelo, the first Spanish colony that pompously called “Ciudad de Nuestra Senora de los Buenos Aires”, that is City of Our Lady of Good Winds in homage to the Madonna who grants good winds to sailors.

De Mendoza was a mediocre soldier and did not enjoy the esteem of his men because in 1527 he had participated in the notorious “Sack of Rome”, enriching himself abundantly by stripping even convents and churches.

The wrath of the Indians was unleashed against the newly born city. It was five years of attacks, sieges, massacres.Mendoza himself fell seriously ill and, after having given to his lieutenant Juan de Ayola the task of going up the rivers already explored by Caboto, and the political powers in Buenos Aires to captain Francisco Ruiz Galan embarked for Spain and died on the journey.

While Ayola continued his exploratory journey (during which he died), his field teacher Domingo Martinez Irala disassociated himself and transported the small group of survivors to the city of Asuncion, founded four years earlier, setting fire to everything that was left behind (1541), freeing only a few pairs of horses which, later repopulating the pampas, constituted one of the colony’s greatest assets.

Under the governorate of Irala an anarchic and infernal government was expressed just as he was violent, bloodthirsty and foul.

In 1542 the new governor Alvaro Nunez arrived, the discoverer of Florida, against whom Irala ordered plots and intrigues until he was imprisoned, sent back to Spain and sentenced. Much later the Council of Indies tried him, acquitted him and also awarded him a pension.

Irala continued with her systems; conquered other territories in Paraguay and in Brazil, thus increasing the power of the Spanish Crown but also making a massacre of “guaranis”.

After his death in 1557, anarchy continued. The power was temporarily divided between the municipal administration, the Cabildo and the First Bishop of Paraguay, Pedro de la Torre, and in this way the situation remained until 1573, when the third governor, Juan Ortiz de Zarate, whose nephew arrived Juan de Garay had recently founded the city of Santa Fè de la Vera Cruz, while Cabrera, governor of Tucuman (then dependent on the Viceroy of Peru) founded the city of Cordoba la Llana. And while flourishing cities like Mendoza, San Luis and San Juan were rising, Buenos Aires had remained as it was under Irala, depopulated and desolate.

Juan de Garay in 1580 left Asuncion with about 300 men, reached the remains now buried by vegetation, of old Buenos Aires and founded the city for the second time, representing the then governor Juan de Torres de Vera. the name was amazing: “Ciudad de la Santisima Trinidad y Puerto de Nuestra Senora de los Buenos Aires”.

De Garay was convinced that more than the buried treasures, it was what could be done on the surface that would give the country the greatest wealth, namely: agriculture and cattle breeding. So he immediately proceeded to assign the lands to the colonists; the great production of flour, tallow, horsehair and leather began which were exported to all the centers of the Brazilian coasts.

Meanwhile, the generation of the Creoles, impetuous and rebellious, who considered himself the absolute master of the territory and began to contest the colonizers, contributed greatly to the repopulation of Buenos Aires. And while de Garay worked hard to allocate land and, therefore, to increase productivity, and consequently wealth, the Creoles overthrew power; but it didn’t last long because the colonists reacted and killed the revolutionaries.

In 1583 while on his way to Santa Fè, de Garay was killed in his sleep by the Indians. The citizens of Buenos Aires asked for the election of one of his nephews as new governor, while the Creoles demanded the installation of Juan Enciso Fernandez.

In 1591, with the departure of Juan de Torres de Vera, the governors Hernando Arias de Saavedra, Fernando de Zarate, Juan Ramirez de Velasco and Diego Valdes y de la Vanda succeeded one another. The latter immediately had to propose restrictions on trade as smuggling had taken hold, especially gold smuggling, which could have ruined official trade through Panama.

Furthermore, he did not fail to inform the King of Spain (1599) that in Buenos Aires, except for meat and wheat, people lived below normal living standards as regards all other basic necessities. And while he was about to obtain some privileges for the enhancement of the port of Buenos Aires, he had to embark on a conflict with the Viceroy of Peru and with Bishop Vasquez de Llano; shortly thereafter he died.

The Creole Hernando Arias de Saavedra was elected governor and interim general of the Rio de la Plata, who was then confirmed for nine years (with the royal permission of 1601). He ruled wisely and when in 1610 Francisco de Alfaro issued ordinances in favor of the Indians, he made himself eager and convinced promoter so much that he deserved the title of “Protector of the Indians”.

He was re-elected in 1615 and under his governorship the Spanish colony progressed rapidly. It extended far north and therefore also included the territory of present-day Paraguay. This, poor in resources, instead of progressing was becoming increasingly depopulated; therefore, to avoid this imbalance in the interior of the country, he carried out his most important political act: he obtained consent from the King of Spain to separate the Rio de la Plata from Paraguay. It was November 16, 1617 when, in fact, the territory was divided into two parts: the Province of Paraguay with the capital Asuncion and the Province of Rio de la Plata with the capital Buenos Aires. Both, of course, under Spanish rule. In this way the foundations of the future Argentine and Paraguayan states were established.

Hernando Arias then retired to Santa Fè where he died in 1634, respected by contemporaries and posterity, rightly considered the founder of the “Argentine Nationality”.

After the death of Philip IV of Spain, several governors followed one another, more or less capable, but above all greedy, who sometimes had connivances also with pirates and privateers, so one of the worst evils of that period was certainly the development of smuggling, of clandestine trade and, on a social level, there was the formation of an independent spirit in the Creoles.

At the same time as the Spaniards, the Portuguese had settled on the Brazilian coasts, looking with a cupid eye at the beautiful Spanish colonies on the Rio de la Plata. In 1679, therefore, they sent an expedition to occupy the left bank of the river and there they founded the Colony of Sacramento.

The following year (1680), governor Josè de Garro, the Spaniards conquered it and made all the colonists prisoners.

Then the Portuguese managed to return, both for the weakness of the King of Spain and for the meddling, diplomat of England. With a treaty of 1681, the membership of Portugal was recognized in the Colony of Sacramento.

Other conflicts arose and the eighteenth century began with another dispute as the governor Juan Valdes de Inclan managed to drive the Portuguese out. However, they returned there by virtue of the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and also managed to expand towards the eastern side of the Plata, to reinforce the positions of Sacramento (1720).

The next governor, Zavala, with the help of Tucuman, Paraguay and the Indians, besieged the fortifications. and the Portuguese were forced to abandon them (1724).

In that same place then the governor built the city of Montevideo.

The governor Zavala, excellent from a military point of view, however, was unable to eradicate the smuggling plague, therefore in 1734 he was deposed and replaced by Miguel Salcedo.

The latter wanted to resume the siege of Sacramento and then the Spanish minister Carbajal, with a secret treaty of 1750, in agreement with Portugal, would take Sacramento in exchange for the Rio Grande del Sud, from Santa Caterina to the borders with Paraguay, including the missions of the Jesuits in the Alto Uruguay of Guayra.

When practicing the treaty, all the Spanish countries of America arose; it went on with continuous changes of owner for several years until with the Treaty of Paris of 1763 the disputed territory was assigned to Portugal.

The struggle revived around the colony of Sacramento. In 1776 Charles III of Spain raised the governorate of La Plata to Viceregno, nominated Viceroy Pedro de Cevallos, sent him with a fleet of 19 vessels and 10,000 men to reconquer the territories, which happened in 1777 with a certain ease. The dispute was definitively closed: the Colony of Sacramento remained to Spain and the Rio Grande to Portugal.

Since, however, de Cevallos was protested by the Portuguese for his rigidity in determining the boundaries, he was called back to his homeland and Juan Jose de Vertiz was sent in his place.

In 1782 the Viceroyalty had its first regional settlement because it was divided into 8 Intendenze, with capital Buenos Aires.

Meanwhile sheep farming and agriculture were developing considerably and the cultivation of vines and olives also assumed some importance, despite the fact that spreading was officially prohibited.

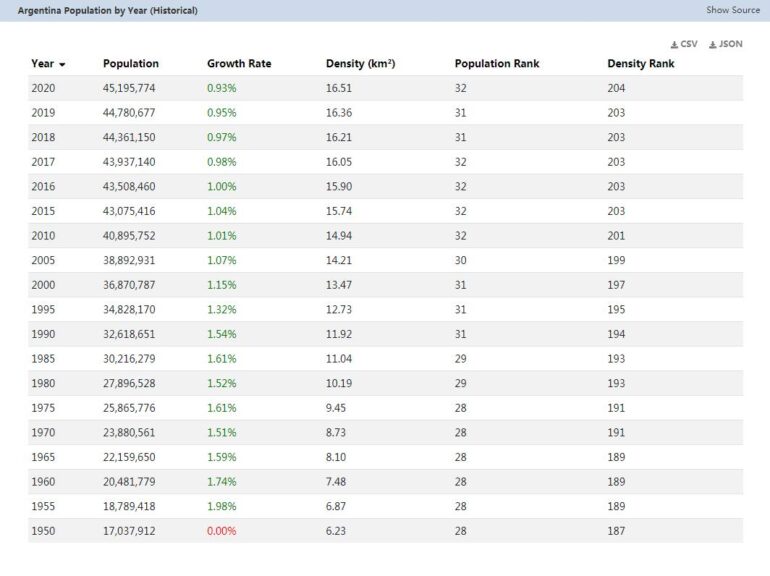

After the authorization to free trade, the port of Buenos Aires expanded, from which most of the export goods departed. In addition, the city itself grew larger and larger. and the population grew rapidly. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Argentina. Even the cities of the interior gradually became more important, first of all Cordoba “the learned”, so called because it housed the University, and the Jesuit College “Monserrat”; and it was also an important Catholic center.

Under the governorate of Vertiz there was the first printing house; with consequent diffusion of books; this was considered at that time a very dangerous act precisely because through the press and the diffusion of culture liberal ideas were fed more, especially among the Creoles for their particular sense of individuality, for their secret antagonism with the Spanish race, for indiscipline and contempt for every rule. All of this was greatly helped by Creole elements.

Always for the great merits of Vertiz there were other steps forward in the progress of both culture and public works including the “Collegio di San Carlo”, the “Casa de Comedias”, the “Ospizio de Mendicita”, as well as the flooring of the whole city. of Buenos Aires.

Vertiz was succeeded by the giftmaker Marquis of Loreto, with clearly contrary ideas, so much so that he attempted to erase everything that had evolved until then.

After him, General de Arredondo resumed his progress by making ample concessions to free trade and to the exchange of all types of goods. In 1794 the traffic of the port had increased considerably and just as important had the merchant fleet become.

The situation improved further with Viceroy Juan del Pino who promoted the establishment of the newspaper “Semanario de Agricoltura y Comercio” and the foundation of the schools of geometry, architecture and design, and boating.

Upon the death of Juan del Pino (1804), he assumed the position of Viceroy the Marquis of Sobremonte.

Meanwhile, with the victory of Trafalgar, the Spanish colonies found themselves in serious danger since in January 1806 the English general David Baird, after conquering the Cape of Good Hope, on June 25 was ready to land in the port of Quilmes, a very short distance from Buenos Aires; on the following day 26 he rejected the few and disorganized militias of Sobremonte, who fled to Cordoba, and on the 27th he entered the capital, very frowned upon by the Creole and colored population.

The defense of the colony then passed into the hands of the French Jacques de Liniers, who reorganized the army, supported by everyone, on 3 August prepared for the counter-offensive; on 4th and 10th he imposed serious losses on the British and on 12th August he regained possession of the city with the surrender of the enemies who therefore had to abandon the company.

Liniers was appointed Military Governor, refused to receive Sobremonte and thinking, with reason, that England would not have accepted this blow with impunity, even for the considerable interests that would have resulted from the possession of that territory, he would return to office. The clashes that followed were very hard; at first, for a false maneuver by Liniers, the British recorded important victories, but the strenuous defense opposed by the Argentine patriots eventually got the better of them. All positions were reconquered to the British who thus had to accept the capitulation offered to them by Liniers. And after a swift exchange of prisoners, the British definitively left Argentine soil.

This great military enterprise meant that Liniers was appointed Viceroy in May 1808 to replace Sobremonte, but he also made a change in the soul of the Creoles. They fought with particular value and then thought that if they were so capable in military enterprises, they would also be able to take over the public affairs; which meant that the idea of independence was creeping into people’s minds.

In mid-August 1808, Ferdinand VII lost the throne of Spain by Napoleon, who sent his commissioner, Marquis of Sassenay, to Buenos Aires to deal with Liniers. Immediately the people, forgetful of its merits, began to oppose it as a foreigner. On 1st January 1809 there was a general demonstration, the Viceroy was forced to renounce the assignment and a Supreme Council was established, composed exclusively of Spaniards, except for two Americans.

The Creole troops tried to make Liniers desist from his resignation but he, from that loyal man who had always been, not wanting to make any gesture of indiscipline, did not join and, therefore, let the power of Viceroy be conferred on Baltazar Hidalgo de Cisneros.

The new Viceroy found a very serious situation; he did not have his faithful armed force, so that he could only in a very small part fulfill his first task which was to disarm and dismiss the Creole militias. The Treasury was facing serious difficulties and he, having not obtained any loan from the Spanish shopkeepers, soon opened the port of Buenos Aires to English trade, which gave the start to an immediate improvement in the economic condition of the country.

In May 1810, while Spain was in a difficult period of internal struggles (consequence of the Napoleonic occupation), the party of the independence activists carried out a kind of coup d’etat and seized power. A Government Commission was appointed, composed of the most illustrious independence activists (including the Italian Castelli) who, as a first act, boarded the Spanish Viceroy Cisneros on a ship and sent him back to Europe. That was the May revolution that gave birth to free and sovereign Argentina.

The town however did not have a peaceful life: until 1835 it was tormented by civil strife. In that year a general, Juan Manuel de Rosas, came to power, who established a fierce dictatorship that lasted 17 years.

He established a special Praetorian militia, the “Mazorca” made up of black thugs and dishonest policemen, who carried out a large number of political assassinations.

The upper classes, who initially willingly renounced freedom as long as a stable and efficient government was formed, soon regretted having made this sacrifice and emigrated, for the most part, to Montevideo.

Rosas was fierce even with foreigners and for this reason he came into conflict with more than one power like France, which in 1838 blocked Buenos Aires, like England and the United States, to which he forbade navigation in the Paranà. Then he declared war on Bolivia and in December 1842 he moved against Uruguay, occupying a large part of it, except the capital Montevideo which, however, besieged for nine long years.

In favor of the Uruguayans, in addition to the Argentine liberals who emigrated there, they also fought numerous French and Italians. ; the latter led by the one who covered himself with glory in many battles, but above all that of San Antonio, Giuseppe Garibaldi.

The hatred of most of the people grew against the tyrant; the liberals increased considerably in number and formed an army, whose leaders were generals Paz and Lavalle. At first there were favorable results that made Rosas tremble, but they did not last long due to inexplicable contrasts between the two generals (Lavalle retired). Rosas regained the upper hand and with it the repressions that became even more ferocious. 1840 was remembered as the worst in Argentina’s history because of the spilled blood. The provinces continued the rebellions; Rosas sent an army headed by General Urquiza to tame the rioters; but the general rebelled, allied himself with Brazil, withdrew the forces besieging Montevideo and at the head of a powerful army marched on Buenos Aires.

On February 3, 1852 he defeated the dictator’s forces at Monte Caseros. Rosas was forced to flee in disguise; he embarked on a ship bound for Southampton where he died at the age of 84 in March 1877. Although he was a bloodthirsty dictator, he conquered the Land of Patagonia for Argentina and gave a significant boost to federal unity; for this reason someone tried to rehabilitate him, naturally in vain.

With the victory of Monte Caseros it was immediately thought of a general pacification which, however, did not occur. While Urquiza was in Santa Fè to prepare the Constituent Assembly with the summoned governors, Buenos Aires rose up against the authorities appointed by Urquiza and organized an autonomous government.

Meanwhile the Constituent Assembly of Santa Fè proclaimed the Constitution to which all the provinces except Buenos Aires joined, which in 1854 had proclaimed itself autonomous. And so it remained until 1859 when Urquiza, who had been elected head of the Confederation, waged war and defeated her in the battle of Cepeda on 23 October. Buenos Aires entered the Confederation in 1862 and became the capital of the Argentine Republic; the Constitution was modeled on that of North America.

General Miter was elected president, a patriot and valiant military man of studies and friend of Garibaldi and in favor of the Italian element (he also translated the “Divine Comedy”)

In 1865 the war against Paraguay began which ended in 1870, without bringing any benefits to Argentina, by his successor Domenico Faustino Sarmiento, elected in 1868.

Under his presidency there were serious unrest in Buenos Aires between the nationalist party, represented by Miter, and the autonomist party represented by Adolfo Alsina.

In 1874 Nicola Avellaneda was elected who governed in a more peaceful period and was able to give impetus to agriculture and industry, the construction of railways and the increase in European emigration.

After him in 1880 General Julio Roca was president who defeated the South Indians and transferred the government to the newly founded city, La Plata. In 1881 Roca also managed to complete an old question of borders with Chile.

In 1886 new elections led to the presidency of Juarrez Celman who, however, was not too lucky since in 1890 he had to face a revolution created by the Civic Union precisely against his government. He had to leave the post to his Vice-President Carlo Pellegrini.

In 1898 Roca returned to power and devoted himself more to the development of public works such as the railways and the expansion of the ports of Bahia Blanca, Rosario and Santa Fè.

Then several other presidents followed. Argentina in the First World War declared neutrality and lived a few decades of tranquility in which it was allowed to develop and progress.