It is difficult to historically reconstruct the origin of the Inca kingdom. With this title the ancient Peruvians called their kings and the main royals with divine attributes, that is “Sons of the Sun”.

According to traditional history, four brothers of the “Ayares” tribes of the Quecha Indians, inhabitants in the Paccaritampu area (about 8 km. From the place where Cuzco then arose), led by Major Manco Capac, left in search of new lands and, tested the land near the Huatanay stream and found it fertile, they settled there, giving rise to the Inca dynasty and Incas was the last and most advanced pre-Columbian civilization in South America.

It was the 11th century. These Indians settled in the south, where they founded the capital of their state, Cuzco, then, gradually, occupied all the territories corresponding to today’s states of Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and northern Chile.

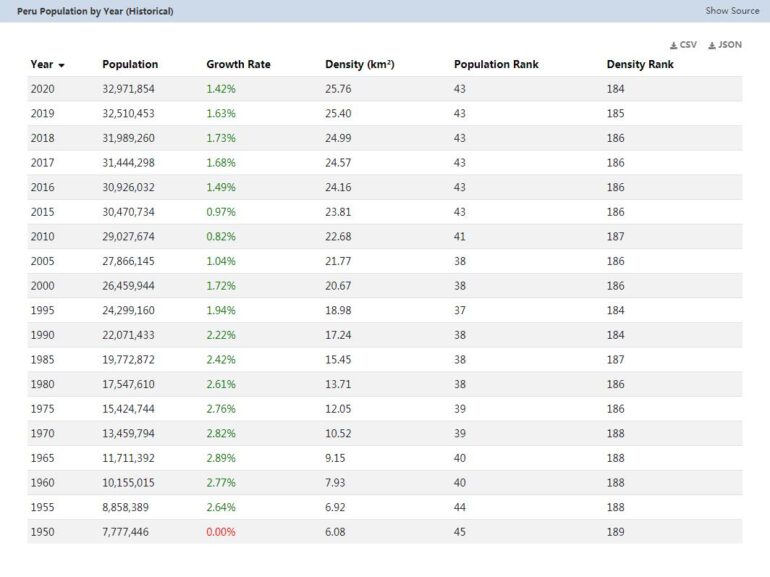

Here they came into contact with other already evolved forms of civilization; they imitated and improved them. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Peru.

The political system of the Inca kings was centralized; hundreds of imperial officials, related to the Emperor’s family, governed the various provinces, controlling agricultural production. And since two thirds of each province was owned by the Emperor, he was entitled to part of the products.

In the “quichua” language, that of the Incas, there was a single verb to indicate work and cultivate. And just the work of the land was first the only activity of the inhabitants.

The agriculture of the Incas was based on the system of terraces, which were formed by many retaining walls raised on the slope of the mountain.

The most cultivated products were potatoes and corn (which the Spaniards later made known in Europe). They were also skilled cattle breeders. One of the animals most frequently bred for the goodness of the meat was a small rodent called “Cuy”; another was the “Guanaco”, derived from the American camel. There were also wild guanacos that the Incas hunted with particular weapons called “Bolas”. They consisted of two ball-shaped stone blocks connected by a very strong rope. The “bolas” were thrown so that they twisted around the animal’s legs which, of course, could no longer escape.

The Incas, however, also bred the “Lama”, suitable for the transport of wagons, the “Alpaca” and the “Vigogna”, both animals with a very soft and fluffy woolly coat with which they wove precious. figurative fabrics, with which traditional, multicolored clothes with precious shades, in particular blue and green, were made.

The production of ceramics was also very rich, with which brightly colored vases were modeled, decorated with floral elements or with stylized animals.

But the most distant traces of the Incas civilization are evident in the surviving monuments of the city of Tiahuanaco, built near Lake Titicaca, or of the fortified city of Machu Picchu. They are ruins of groups of houses built with huge blocks, with grand stairways and terraces. While in the center of Pachacamac, south of today’s Lima, the memory of the grandiose “Temple of the Sun” survives, the most revered divinity in the cult of the Incas. The buildings of the Incas were beautiful, harmonious and, above all, grandiose, imposing. It has never been possible to understand how the Incas, without cars, towing animals, iron to shape the blocks, nor level or team and not even lime, were able to erect houses and buildings, plus an unimaginable luxury for those times.

The Incas used stone tools and the only metal they knew was bronze.

They were also very skilled in making containers of various shapes, decorated and all equipped with handles. Precisely for this reason they hung them by means of ropes to some kind of stone pegs that were inside the houses, fixed in the walls.

Furthermore, given that the great extent of the Empire was mainly in the sense of length, a perfect road network was imposed. And in fact thousands of kilometers of roads were built across the Andes. One of those roads from Cuzco to Quito, the capital of Ecuador, reached 2000 Km. And in some places it was even 8 meters wide. When a road skirted a precipice, tunnels were dug to allow humans and animals to pass. Some of these roads are still accessible by car.

In the mountain stretches, stone steps were built, and the suspension bridges that could be crossed only in single file were made of agave fibers. On these roads, the very fast “Marathon runners” who carried the orders of the Inca to every location in the Empire, to overcome the immense effort, continually chewed coca leaves.

Among the Incas, the only writing system was the “Quipu”. It consisted of ropes and cords of various colors, equipped with knots. The colors referred to certain objects (people, enemies, farmers, products, etc.); the nodes instead indicated dates and numbers that could be calculated based on their position and distance from the beginning of the string. The various officials of the Empire administered the various provinces with the help of these simple tools.

In the archive of the “Provincial Offices” there were as many “quipu” as there were citizens and on them was marked everything that concerned each individual: his profession, the goods he owned and the products he had to deliver as a tax. It was, in short, a kind of “Tax Folder”.

Tragic was the fate that the Incas suffered.

Discovered by Pasquale de Andagoya in 1522, Peru (so called by the small river “Birù”) was then ruled by Atahualpa. The fame of his wealth reached the ears of two captains of the Spanish army in Panama: Francisco Pizarro (1475-1541) and Diego de Almagro (1475-1538).

Determined to take possession of that wealth, at the end of 1530 Pizarro moved from Panama with an army of a few hundred men, a few cannons and twenty horses.

Atahualpa was taken prisoner and strangled. Many thousands of his subjects died with him.

Soon Pizarro conquered the whole country, but then he had to endure a civil war with Diego de Almagro who, enviously, demanded the government over all the lands he conquered. Pizarro came out victorious and had his rival tried first and then put to death.

Then he founded Lima, which he first called “Ciudad de los Reyes”, that is “City of the Kings”, and then renamed Lima, in honor of Santa Rosa da Lima, declaring it the capital. He settled there but only three years after Almagro’s death he was also assassinated.

The death of Pizarro (1541) was caused by a fierce struggle that broke out between his captains over the division of the lands. This continued until 1542 when Emperor Charles V, worried about the turbulence of the colony, created the Viceroyalty of Peru with an ordinance and sent the energetic Viceroy Andres Hurtado de Mendoza to America. Some beheadings brought calm and order back and the colony began to progress.

For a long time the Incas, who had obtained the consent of the Spaniards to elect their own sovereign, continued their attempts at rebellion, as long as they broke their race spirit, they too fell into that irreducible fatalistic apathy, which is still the characteristic of the few surviving Peruvian Indians.

New cities arose in place of the old destroyed ones and the economic life of the country underwent a profound variation. In fact, new crops were introduced, such as that of coffee, but at the same time the dangers of large estates and parasitism began to spread. The ethnic base of the Andean region itself had radically changed because the Spaniards had imported Negro labor. So the people found themselves to be a mixture of Spanish, Indian and Negro. But also some old ways of living and some old beliefs mingled with the new faith, the new religion, the new language, new customs and habits creating a rather bizarre environment.

In 1571 a rebellion of a descendant of the Inca kings was stifled, with the usual system of beheading, and the life of the Viceroyalty for two centuries had no other shocks.

The mining industry was greatly developed, which became the country’s main economic activity; large deposits of gold and silver were discovered and intensely exploited.

The missions of Jesuits and Dominicans, meanwhile, went increasingly inward to carry out a beneficial work of assistance to the “Indians” who had always been a disheartened and miserable mass.

In 1739 the Viceroyalty of New Granada was detached from Peru, then Colombia, with the capital Bogota and in 1776 King Charles III detached the “Real Audiencia de Charca”, today Bolivia.

In the Viceroyalty of Peru, as indeed in the other Spanish colonies, some groups of people began to spread the idea of autonomy and independence from Spain. The first attempt at rebellion occurred in 1806, but it failed and the two main perpetrators were executed. To avoid the repetition of revolts, Spain strengthened its dominion but, both the “Creoles” and the “Mestizos”, strongly hostile to the “Peninsulares”, that is to the Spanish, encouraged by the news of the French Revolution, but above all by the coup de grace that Napoleon had given to Spain (l808), they tried by every means to gain independence. However, the social structure of these territories, on the one hand rich landowners indifferent to any other perspective, on the other the incalculable mass of poor peasants,

As long as, Peru’s time came in 1820: in the summer of that year, General San Martin, hero of Chilean independence, landed on the Peruvian coast with an army made up of Argentines and Chileans and attacked the Spanish stronghold of Lima. On July 28, 1821 the so-called “Army of the Andes” occupied the capital and proclaimed the independence of Peru.

Since, however, the Spaniards still occupied a large part of the country and the coasts, the Peruvian patriots asked Simon Bolivar, the liberator of Colombia, who entered the country with a small Colombian army, reorganized their forces with hard and long work. Peruvian and on August 6, 1824 attacked the Spaniards in Junin, 150 km. northeast of the capital and routed the Spanish army.

On 9 December 1824 General Antonio Josè de Sucre, lieutenant of Bolivar, defeated a second Spanish army and with this victory the Spanish domination over Peru ended, which became Republic.

The new Peruvian Republic did not have an easy life. Until 1845 there was a period of internal struggles between the various leaders and some attempts to establish a large Peruvian-Bolivian Confederation. In that year General Ramon Castilla came to power, who gave the country its first state order and real economic progress.

In 1862 Peru rejected an attempt by Spain to recover the lost colonies and since then, save for a disastrous war against Chile in 1879, Peru did not see any other events happening.

For decades chiefs and presidents succeeded one another in overthrowing their predecessors and in turn being driven out or murdered.

After continuous internal unrest, Peru had a clever and intelligent leader in President Augusto Leguia (1919-1930), who gave the country order and well-being and in December 1927 Peru defined the borders with Colombia, in 1929 those with Chile for the territories of Tacna and Arica.

The government of Leguia was overthrown in 1930; troubled years followed characterized by the contrasted dictatorship of Oscar Bonavides (1933) and by conflicts with Ecuador, again for border issues which led to the signing of an agreement between the two governments on March 12, 1936, for the appointment of a commission charged with work out the precise boundaries in the Zarumilla region.

A pact of friendship and non-aggression was signed with Bolivia on November 9, 1936. Also in that year, presidential power was extended by 3 years to General Bonavides who continued, even after a revolutionary plot, discovered and repressed, to support the country’s economic and social progress.

And while pacts and treaties had been consolidated with all the neighboring states, the border conflict with Ecuador remained in place until relations completely ceased in 1938. At the end of that year the Eighth Pan-American Conference met in Lima.

With the outbreak of the war in Europe, Peru declared itself neutral. Within the country Bonavides found himself forced to govern with rather rigid methods but pursued his work aimed at financial reorganization, and at the completion of a vast project of public works and social legislation. He favored the production of wheat even if the main food was rice; established the Ministry of Education; reopened the autonomous universities that had been closed due to student unrest; he prepared the census and in 1939 called some referendums to start constitutional reforms and called new elections.