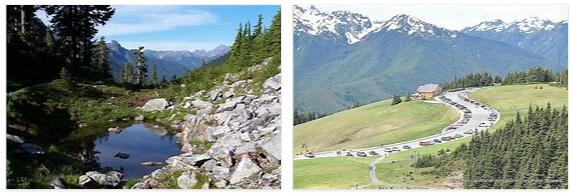

The park has a variety of landforms and ecosystems. The highest point is Mount Olympus with 2428 m. Original rainforest, mountain forest and sub-alpine areas as well as snow-capped peaks form a varied landscape with a rich flora and fauna. These include Roosevelt deer, black bears, lynxes, coyotes, raccoons, skunks, mountain beavers, marmots or river seals.

Olympic Mountains National Park: Facts

| Official title: | Olympic Mountains National Park |

| Natural monument | National park since June 29, 1938, expansion to include Pacific Coastal Area and Queets River Corridor in 1953, to include Point of Arches and Shi Beach in 1976; since 1976 biosphere reserve with an area of 3696.59 km², heights up to 2428 m, Olympic Mountains as the highest mountain range directly on the Pacific |

| continent | America |

| country | USA, Washington State |

| location | Olympic Peninsula, northwest Washington State, near Seattle |

| appointment | 1981 |

| meaning | a particularly large variety of landscape types and ecosystems, the largest preserved area of an original rainforest in the temperate climate zone in the western hemisphere |

| Flora and fauna | five vegetation zones: »temperate rainforest« with sitka spruce, western hemlock, giant arborvitae and large-leaved maple, lowland forest with coastal fir, Douglas fir, mountain forest with Douglas fir and purple fir, subalpine region with mountain hemlock and subalpine mats as well as glacial alpine region; 50 species of mammals, including an estimated 5000 Roosevelt elk, up to 300 mountain goats, as well as pumas, black bears, the yellow spruce chipmunk, which belongs to the squirrel, Olympic marmot, Olympic Mazama pocket rat; 180 species of birds such as the peregrine falcon and the spotted owl |

Record-breaking rainforests on the Pacific

The diverse sanctuary of the huge Olympic Peninsula to the west of Seattle extends from dripping, lush green rainforests to lush mountain meadows, from the wind-swept Pacific coast to the snowy summit of the 2,428 m high Mount Olympus. It encloses the majority of the “Olympic Mountains” and an approximately 90 kilometers long, narrow strip along the Pacific Ocean.

While the highest heights of the Olympic Mountains are covered by dozens of smaller glaciers, a dense forest extends in the lower elevations of the mountains. Especially in the western valleys of the Hoh, Queets and Quinault rivers, a mild climate, the fog coming from the Pacific and three to four meters of precipitation per year created ideal conditions for the growth of a »temperate rainforest«.

The unique plant formation is dominated by mighty conifers, mainly sitka spruces with conical growth, Douglas firs with rough, cracked bark, western hemlock with slender, mostly hanging shoots and scale-leaved giant trees of life. Some of them are among the largest of their kind: A Douglas fir in Queets Valley, for example, reaches a height of 60 m and a base circumference of 13.5 m. The large-leaved maple is also typical and thickly overgrown with mosses and ferns. He usually carries his heavy load with composure, because he benefits from his “guests”. With the help of small branch roots, it removes vital nutrients from the epiphyte cushions. If such a rainforest giant falls, it becomes a “nurse tree”, the nurturing mother of young trees that grow more easily on it than on the one with wood sorrel, Sword ferns and horsetail gain a foothold on the forest floor. Some seedlings use the old stumps and send roots from this airy seat down to the ground, on which they then stand as if on stilts.

The long ice age isolation of the peninsula has left its mark on the park’s fauna. While typical residents of the nearby mainland mountains such as the pika and gold-coated ground squirrel are missing, on the other hand there are species or subspecies that only occur here, such as the Olympic marmot, the Roosevelt elk and the black-tailed deer. The stubby-tailed or beaver squirrel, which is only 30 to 40 cm long, is one of the more interesting mammals. It is limited in its distribution to the Pacific coastal mountain forests between central California and the Canadian state of British Columbia.

Seals and occasional Steller’s sea lions can be seen on the driftwood-strewn beaches of the Pacific coast. Thanks to a reintroduction program, the sea otter has been at home again for several decades. From exposed points you can see mighty gray whales pass by in autumn and spring. Bald eagles and bering gulls also hunt for food on the Pacific coast, and the picturesque rock towers in front of it serve as nesting grounds for guillemots and rhinoceros.

The tranquility of the forests is disturbed by the hammering of the helmet woodpeckers, which punch their large, rectangular nesting holes in the trees. Rock mountain fowl and rose-bellied bullfinches prefer the higher elevations up to the snow line. There, red-tailed buzzards and ravens can also be carried over the cliffs by the updrafts.

Probably the hunters and gatherers who roamed the area 12,000 years ago were the “discoverers” of the Olympic Peninsula. Ten thousand years later, representatives of the Makah culture lived on the peninsula. The first “pale faces” probably reached the peninsula at the end of the 16th century. Two centuries later, the “white man” began the unbridled overexploitation of the rich coastal forests, which was only stopped when the national park was founded in 1938. Today the capital of the Olympic Mountains lies in “soft tourism”; Strolling under the green moss curtains of the »Hall of Mosses« and enjoying the lupine-strewn mountain meadows is a pleasant change from everyday life for the majority of stress-ridden city dwellers.